New Delhi: You might not need an extensive sensor network or a host of volunteers to detect earthquakes in the future -- in fact, the lines supplying your internet access might do the trick.

Researchers at the Stanford University have developed technology that detects earthquakes using fiber optic lines. In case of seismic activity, laser interrogators detect disturbances in the fibers and send information about the magnitude and direction of earthquake tremors.

The system can not only detect different types of seismic waves (and thus determine the seriousness of the threat), but spot very minor or localized quakes that might otherwise go unnoticed.

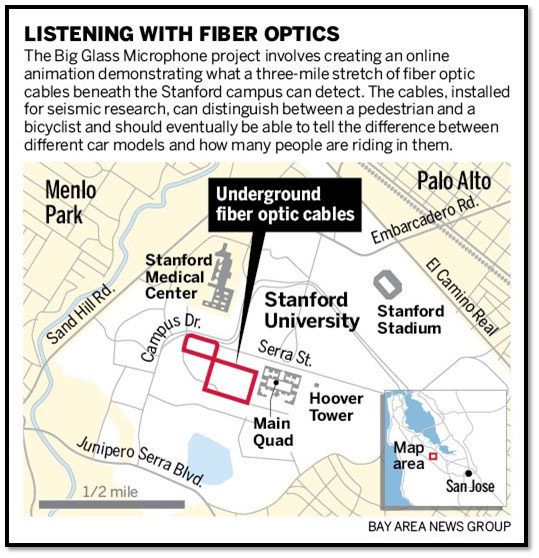

Miles of fiber-optic cables have been buried under the Stanford campus for years. They transmit digital data and Internet traffic at high speed to the students and faculty.

Basically, optical fibers are thin strands of pure glass about the thickness of a human hair. They are typically bundled together to create cables that transmit data signals over long distances by converting electronic signals into light.

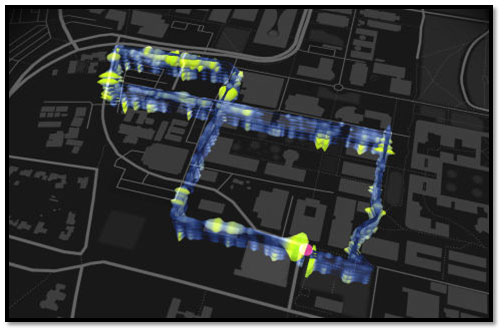

BiondoBiondi, a Geophysics professor at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciencesrepurposed some of those cables, along with an existing underground network of sensors, to create a virtual three-mile-long, figure-eight-shape subterranean seismometer.

A breakthrough came when he discovered that the fiber wires themselves could detect seismic vibrations.

University’sresearchers’ team also added that the fibers can distinguish between the two types of earthquake waves, the P-wave and the S-wave. This is crucial for earthquake warning system because P-waves travel faster but S-waves cause more damage. Detecting the P-waves early is pivotal in predicting earthquakes.

Since the fiber optic seismic observatory at Stanford began operation in September 2016, as per the report published in the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Spectrum;it has recorded and cataloged more than 800 events, ranging from manmade events and small, barely felt local temblors to powerful, deadly catastrophes like the recent earthquakes that struck more than 2,000 miles away in Mexico last month. In one particularly revealing experiment, the underground array picked up signals from two small local earthquakes with magnitudes of 1.6 and 1.8.

But Biondi is not the first to envision using optical fibers to monitor the environmentisn't strictly new; a technology known as distributed acoustic sensing (DAS) already monitors the health of pipelines and wells in the oil and gas industry.

The previous implementation of this kind of acoustic sensing, however, required optical fibers to be expensively affixed to a surface or encased in cement to maximize contact with the ground and ensure the highest data quality.

In contrast, Biondi’s project under Stanford — dubbed the fiber optic seismic observatory — employs the same optical fibers as telecom companies, which lie unsecured and free-floating inside hollow plastic piping.

Though this aspect of optic fiber technology as mentioned- is already used by oil and gas companies, this study is the first comprehensive look at how to implement it on a wider scale. The companies use the fibers by attaching them to a surface, like a pipeline, or encasing them in cement. The team, however, used loose fiber optic cables lying inside plastic pipes, mimicking a standard optical communications installation.

Challenges to make this a reality:

The fiber optic seismic observatory at Stanford is just the first step toward developing a Bay Area-wide seismic network. There are still many hurdles to overcome such as:

It's limited by the size of the fiber network, so it could miss rural areas that don't have much if any fiber.

And the current proof of concept is a relatively modest 3-mile loop around Stanford University.

It could be a much more daunting prospect to run a sensor network across an entire city, let alone cross-country.

This could still be far more affordable than rolling out dedicated sensors, however, and the sheer precision of using fiber (every part ofthe line counts) could provide earthquake data that hasn't been an option before.

Currently researchers monitor earthquakes with seismometers, which are more sensitive than the proposed telecom array, but their coverage is sparse and they can be challenging and expensive to install and maintain, especially in urban areas. But such a network would allow scientists to study earthquakes, especially smaller ones, in greater detail and pinpoint their sources more quickly than is currently possible. Greater sensor coverage would also enable higher resolution measurements of ground responses to shaking.

Perhaps the most promising part of this research is the fiber array’s ability to record the faint, fastest waves from a distant quake — called P waves — which arrive before the ground begins shaking.

Could this someday become part of a relatively cheap and ubiquitous earthquake early-warning system?

References:

https://www.inshorts.com

https://www.engadget.com

http://sanfrancisco.cbslocal.com

https://news.stanford.edu

http://www.ibtimes.com

http://indianexpress.com/