New Delhi:In a new research; Astronomers, using data collected from European Southern Observatory (ESO) telescopeshave discovered two exoplanets larger than Earth orbiting a red-dwarf star located about 111 light-years away in the constellation Leo.

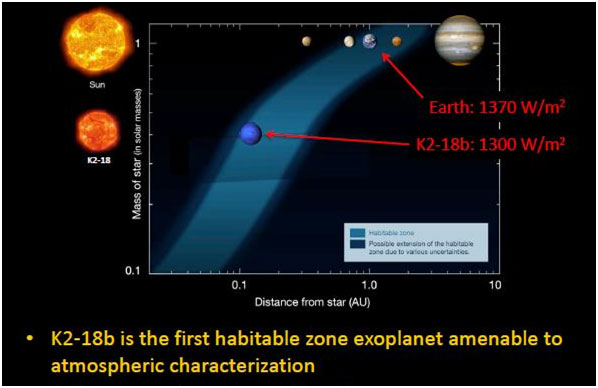

The research team who discovered the planet K2-18b back in 2015, noted that it lies with the habitable zone. Since K2-18b is likely rocky, this means the planet could have liquid water on its surface, which is one of many conditions for supporting life.

But if that weren’t exciting enough the team then realised that their newly discovered super-Earth wasn’t alone and in fact had a neighbour.

“Being able to measure the mass and density of K2-18b was tremendous, but to discover a new exoplanet was lucky and equally exciting,” explains lead author Ryan Cloutier, a PhD student in U of T Scarborough’s Centre for Planet Science.

Although, one planet i.e, K2-18b was first observed in 2015 within the star's habitable zone;the second planet popped up when Cloutier noticed a different signal in the data than from K2-18b, which orbits its star every 33 days. The second signal happened every nine days. After ruling out the possibility of noise, the astronomers announced a second planet called K2-18c. The planet is also a super-Earth, but likely orbits too close to its parent star to have liquid water on its surface.

“When we first threw the data on the table we were trying to figure out what it was. You have to ensure the signal isn’t just noise, and you need to do careful analysis to verify it, but seeing that initial signal was a good indication there was another planet,” Cloutier says.

Although K2-18b was actually discovered two years back, it is only now that researchers were unsure if K2-18b was a super-Earth — meaning it is slightly larger than our planet, but mainly rocky — or a mini-Neptune composed mostly of gas.

Therefore, figuring out which is actually true will require more observations, and that time the data set used by the researchers came from the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) using the ESO’s 3.6m telescope at La Silla Observatory, in Chile.

HARPS allows for measurements of radial velocities of stars, which are affected by the presence of planets, to be taken with the highest accuracy currently available. Hence, this instrument allows for the detection of very small planets around them.

In order to figure out whether K2-18b was a scaled-up version of Earth (mostly rock), or a scaled-down version of Neptune (mostly gas), researchers had to first figure out the planet’s mass, using radial velocity measurements taken with HARPS.

“If you can get the mass and radius, you can measure the bulk density of the planet and that can tell you what the bulk of the planet is made of,” saidRyan Cloutier.

After using that, what they found was really exciting. Cloutier and his team were able to determine the planet is either a mostly rocky planet with a small gaseous atmosphere – like Earth, but bigger – or a mostly water planet with a thick layer of ice on top of it.

But, “With the current data, we can’t distinguish between those two possibilities,” he said.Current technology prevents us from being able to definitively say which one it is but the fact that it could be either is a huge leap forward in our understanding of this distant solar system.

On the other hand, similar in size, K2-18c is sadly too close to the star for it to be habitable but the researchers believe it could still be of a similar size and composition to its more distant relative.But thankfully, the research team won’t have to wait long before they get their answer as NASA’s replacement for Hubble the James Webb Telescope, will be able to tell them one way or the other, which is set to launch in 2019.

“It wasn’t a eureka moment because we still had to go through a checklist of things to do in order to verify the data. Once all the boxes were checked it sunk in that, wow, this actually is a planet.”

Cloutier collaborated with an international team of researchers from the Observatoire Astronomique de l’Université de Genève, the Institute for research on exoplanets (iREx), Université de Grenoble, U of T Scarborough, and Universidade do Porto.

Other researchers on the team are affiliated with the Geneva Observatory in Switzerland, France’s University of Grenoble, and the University of Porto in Portugal. The research will be published in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics and is currently available on the website Arxiv.

References:

https://www.spaceanswers.com

http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk

http://www.newsweek.com

http://www.mirror.co.uk

https://www.infowars.com